Hong Kong SAR, by virtue of its geo-political position, has always been an integral shipping port for global trade and commerce. The city is one of the world’s leading cargo transhipment ports which manages on an annual basis over 4m tons of air cargo and 24m TEU of ocean freight.”[1]

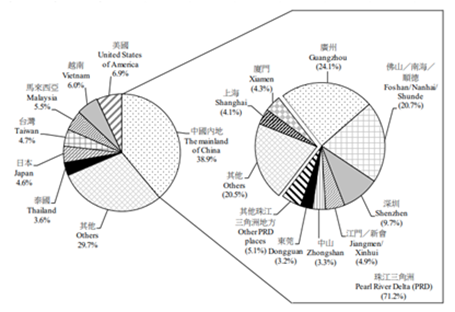

Among major countries and territories, port transhipment cargo movements between Hong Kong SAR and Mainland China continue to take up the largest share (38.9%) of Hong Kong’s port transhipment cargo in 2017, with the bulk (71.2%) of these shipments from Mainland China coming in from the neighbouring Pearl River Delta as demonstrated in the chart below:

Figure 1:

Source: Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics: Port Transhipment Cargo Statistics, 2007 to 2017

In terms of commodities being shipped, “manufactured goods” took up the largest share of transhipment cargo movements which was 31.2% (44,718 thousand tonnes) in 2017. Other commodities pertained to crude materials; chemicals and related products; food, beverages and tobacco; machinery and transport equipment; mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials; and animal and vegetable oils, fats and waxes.[2]

Hong Kong as a major source of IP infringing products

Based on the Report on the EU Customs Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights, Mainland China is still the main source for goods suspected of infringing one or more intellectual property rights arriving in the EU. [3]

Surprisingly, in certain product categories, Hong Kong SAR was found to be one of the main sources of suspected IP infringing goods. These specific categories included watches, mobile phones and accessories, ink cartridges and toners and CDs/DVDs despite it being highly unlikely that the territory is manufacturing any of these products mentioned. Overall, it was estimated that Hong Kong SAR was the source of 9.43% of infringing goods entering the EU, whilst Mainland China remains the preeminent source of infringing goods at 50.55%.

The statistics are even higher when it comes to counterfeit goods entering the United States. “In the fiscal year 2019, around 66% of the counterfeited products seized due to IP rights infringement in the US originated from China, with Hong Kong SAR then being the second highest source at 26%.[4]

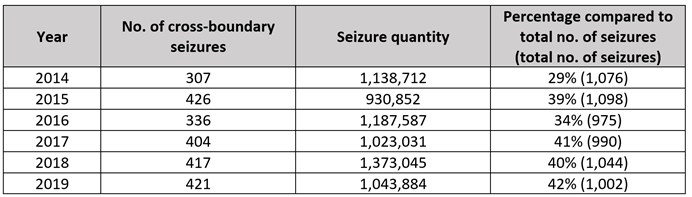

A survey of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection intellectual property rights seizure statistics (shown in the table below) reveals that from 2014-2019, Mainland China remains to be the biggest source of infringing goods in the United States with Hong Kong following a close second year after year.

Table 1:

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection Seizure Statistics

The above information on Hong Kong’s position as a key source of counterfeits for both the EU and the US is surprising for a territory which has firmly cemented itself as a financial services hub, with very little manufacturing output.

The data suggests that Hong Kong SAR is being used as a transhipment hub for counterfeit goods originating in Mainland China, before the goods are then shipped to end user countries such as the US and EU. The EU data indicates that almost 71.2% of the counterfeit goods entering Hong Kong SAR from Mainland China are coming from the Pearl River Delta. This suggests large volumes of counterfeit goods are likely being sent directly from factories in the surrounding provinces straight into Hong Kong SAR for shipment out to the world.

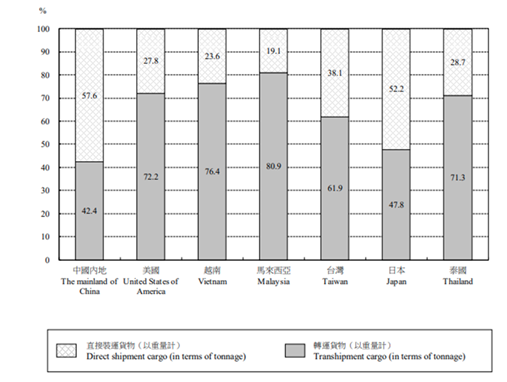

The graph below shows that in 2017 alone, the volume of transhipment cargo movements surpassed the volume of direct shipment cargo movements between Hong Kong SARand major economies. As shown below, 72.2% of port cargo movements between Hong Kong SAR and the United States were transhipments, compared to 76.4% for Vietnam and 80.9% for Malaysia.[6]

Figure 2:

Source: Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics: Port Transhipment Cargo Statistics, 2017

IP Enforcement in Hong Kong SARand the Hong Kong Customs & Excise

Hong Kong’s main advantage in IP enforcement is that it has developed a comprehensive and effective legal framework for the enforcement of copyright, trademarks and registered designs with a wide range of enforcement measures available including civil action, criminal action and customs enforcement.[7] Such measures have had considerable success in combatting the proliferation of infringing products especially with the actions taken by the Hong Kong Customs & Excise department.

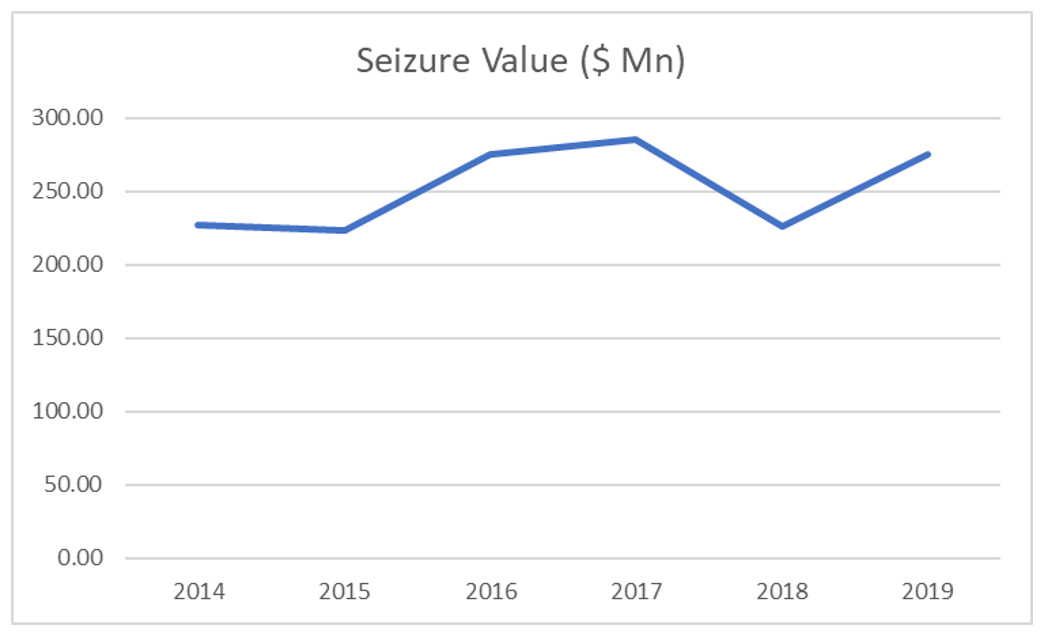

In looking at the achievements of HKC&E in intellectual property enforcement, we have reviewed and analysed the various press releases[8] that have been issued by the HKC&E for the period of 2014 to 2019. From the information provided, we were able to chart the total seizure values of the detained commodities as shown below:

Figure 3:

Source: HKC&E Press Releases

Most of these goods are clothing, footwear, mobile phones and accessories, and other fashion accessories which have likely originated from China, to then be exported to the United States or Europe.

The information below shows the number of trade mark infringement seizure cases conducted by Hong Kong Customs on cross-boundary goods, i.e., goods seized from different entry or exit points in Hong Kong SAR including airport, container terminals, etc., originating from Mainland China.

Table 2:

Source: HKC&E and HKC&E official statistics

This information supports the fact that a substantial number of infringing goods pass through Hong Kong SAR borders coming from Mainland China even though some are not intercepted and manage to find its way in the US or EU. In recognition of this, HKC&E has been working closely with China and Macao Customs, along with the US and EU, to combat cross-boundary counterfeiting activities.

What an IP owner can do

Notwithstanding the achievements of the HKC&E, it can only do so much especially if there is no support from the intellectual property owner. The support needed by HKC&E is the application by the IP owner for registration of its intellectual property rights with the Intellectual Property Department (“IPD”), Customs recordal of its duly registered IP rights, and its active participation in the enforcement actions taken by HKC&E.

HKC&E employs one of the most stringent and cumbersome Customs recordation processes compared with other jurisdictions. Yet, once this rigorous recordation process is overcome, IPR owners immediately realize the benefits since there is no bond or guarantee required by HKC&E to detain infringing goods. Apart from the logistical support in examining the seized goods or in limited instances that an examiner is called upon to testify in Court, the IP owner does not incur exorbitant legal expenses in going after infringers through HKC&E enforcement action.

On the contrary, the IP owner even benefits as HKC&E often conducts its own independent probe on suspected counterfeiters based on reports of the IP owner or the general public. The information that may be shared by HKC&E is integral for IP owners to understand the infringement situation and make the corresponding actions to protect its IP.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that Hong Kong SAR plays a strategic role in terms of combatting IP infringing goods. Hong Kong SAR may not be a direct source of IP infringing products, but it is being utilised as a jump off point for these goods to reach other markets. For IP owners, this means that the global supply of infringing goods may be cut-off in Hong Kong SAR if the right actions are taken.

[1] Mark Millar, “The World’s Leading Cargo Transhipment Hub”, <http://www.hongkongmaritimehub.com/the-hub/the-worlds-leading-cargo-transshipment-hub/> accessed 14 January 2021.

[2] Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR, “Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics: Port Transhipment Cargo Statistics, 2007 to 2017” (2018) <https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71812FB2018XXXXB0100.pdf> accessed 14 January 2021.

[3] European Commission, “Report on the EU Customs Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights” (2018) <https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/2019-ipr-report.pdf> accessed 14 January 2021.

[4] Errin Duffin, “Breakdown of the Source Economies of IPR Infringing Products U.S. FY 2019” (2020) <https://www.statista.com/statistics/328788/breakdown-of-the-source-economies-of-ipr-infringing-products-in-the-us/> accessed 14 January 2021.

[5] MSRP means manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

[6] Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR, “Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics: Port Transhipment Cargo Statistics, 2007 to 2017” (2018) <https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71812FB2018XXXXB0100.pdf> accessed 14 January 2021.

[7] Hank Leung, “Snapshot: Intellectual Property for Fashion Goods in Hong Kong” (2020) <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=deefd82b-7319-4200-bb04-c38d18cb2326> accessed 14 January 2021.

[8]Customs & Excise Department <https://www.customs.gov.hk/en/publication_press/press/index_year_2020.html> accessed 14 January 2021.