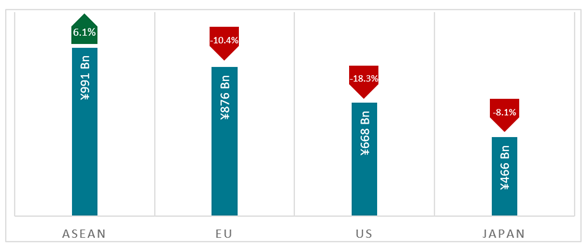

Over the last 5 years, bilateral trade and economic cooperation between China and the ASEAN region has continued to show steady growth. In 2020, the ASEAN region became China’s largest trading partner, overtaking the EU, for the first time.

China’s Foreign Trade with key partners, Q1 2020 (In billion RMB)

Source: GACC

Growing internet penetration and ecommerce trade has led to a significant increase in the number of small airfreight shipments (through large postal and courier hubs) to the region.

The complexity of this channel has increased leading to a wider range of counterfeit goods channels of trade, challenging large sea freight containers as the main means of shipping counterfeits to the region.

The import and export trade in counterfeits is part of a wider trade in grey goods (alcohol, tobacco and other highly taxed goods) and illicit goods (people, narcotics, synthetic drugs, medicines, firearms, timber wildlife) which is prevalent in SE Asia, as well as a problem in legal trade through non-compliance with regulations and payment of tariffs and duties.

Weak border regimes, a long and porous land border and a lack of oversight, compounded by corruption, contributes to this trade in illegal goods. Counterfeiting does not exist in a vacuum and needs to be addressed as part of an overall strategy to improve customs effectiveness at preventing all kinds of illicit goods. This will mean partnering with organizations that are also seeking to stop human, wildlife, narcotics, contraband and other trafficking.

CHINA CONTINUES TO BE THE GLOBAL SOURCE OF COUNTERFEIT GOODS EXPORTED WORLD-WIDE AND TO SE ASIA

China’s role in counterfeit trade cannot be overseen. Counterfeit goods from China are estimated to make up approximately 12.5 % of China’s total exports and over 1.5 % of its GDP. Several comparative analyses rank the region as the primary source of global counterfeit goods (up to 75% of all counterfeits). Data also suggests that the size of the trade of counterfeit goods from China into SE Asia is approximately USD35 billion. The volume poses significant harm to developing economies within South East Asia where local businesses and investors suffer heavy losses due to such activities.

Free Trade Zones (FTZs) and Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are vital for global trade. They support numerous industries and provide many different functions. Many countries in SE Asia have FTZs and SEZs. Several reports suggest that FTZs and SEZs are actively supporting illicit and counterfeit trade. FTZs are used to hold, redistribute and facilitate the trade in counterfeit good, whereas SEZs allow the reprocessing of goods so unbranded packaging can be shipped and then rebranded and packaged for onward transit.

The lack of applicability of domestic laws, and inaccessibility, as well as a lack of oversight from Customs, has led to an environment that enables illicit activities to infiltrate the zones. More needs to be done to raise concerns during counterfeit trade discussions, to increase transparency, and to develop fresh codes of practice on illicit goods. IP owners and governments need to engage with China to create a process or structure in which China can work with its SE Asian trade partners to effectively address the issue.

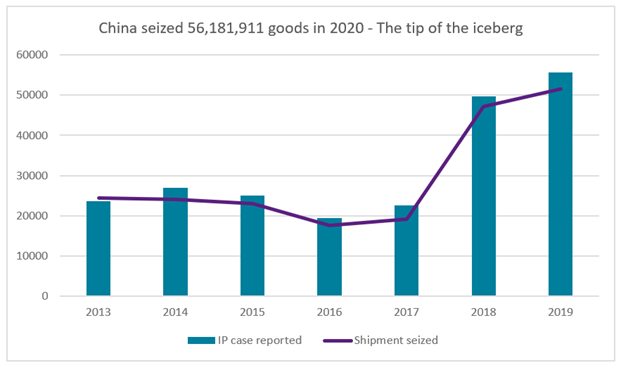

China

China has a sophisticated recordal, data collection and analysis systems in place. The number of IP rights recorded with China Customs has increased YOY with over 26,000 IP owners now using the system. The number of seizures conducted by China Customs, continues to grow YOY with over 61,000 seizures in 2020. However, only around 1,000 IP holders had successful customs seizures (which represents around 4% of the total number of IP holders with recordal) and the quality of the shipping information provided by Customs to IP owners and the criminal authorities on suspect shipments and confirmed counterfeits is limited.

Customs in China needs to continue to improve detection systems as well as improve the quality, quantity and veracity of the shipping information it obtains and shares with IP holders to enable further investigations and legal actions. IP holders need to support Customs by providing greater information, intelligence and training to improve targeting. Additional improvements to the system include minimising storage / warehouse / destruction obligations and costs by speeding up the investigation process, as well as reducing the need for bonds (as indemnities to meet any costs of improper behaviour should suffice).

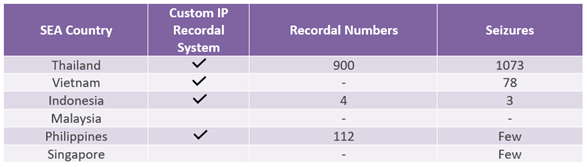

SEA

SE Asian countries have widely varying levels of Customs IP border protection, but apart from Thailand very few counterfeit goods are being seized. The tiny number of recordals and seizures in the region, as compared to regions of similar proportions (such as the EU and China) suggests almost no attempt to impede the flow of counterfeits. The total number of seizures is estimated around 1,500, with 1,000 of them occurring in Thailand. Some countries have no effective system like Malaysia and Indonesia. Other countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam need to improve the current systems.

There is a growing need to invest in extensive IP border protection regimes. A clearer focus on the policy reasons to address the issue is needed within SE Asia’s highest levels of government (such as Ministries of Finance which overseas Customs). Customs training and capacity building should follow after the country has increased seizure capabilities.

Customs IP border systems are generally based on the adoption of international rules that rely heavily on the IP owner and the court system to identify, police and punish infringers, respectively. This has led to an ineffective Customs IP border regimes in the region (and elsewhere). The recordal and ex officio seizure systems offered in the UK and China (as well as US and Europe) whereby suspect goods are flagged and reported to IP owners, then quickly seized, is the industry gold standard. Only Thailand has such a system working effectively.

The UK and China are well placed to support regional Customs IP border protection regimes by introducing an alternative, more practical approach based on their systems and combined expertise and experience.

Counterfeit goods from China are flowing into SE Asian countries remain largely unchecked. The harms from these counterfeits in SE Asia markets come in a variety of forms. Some pose dangers to consumers (in the form of counterfeit pharmaceuticals and other poor quality, hazardous items), while others negatively impact the local economy (in the form of reduced tax revenue, lost legitimate sales and jobs, and incrementally higher costs). Counterfeiting straddles both the grey and underground economies as well as a harmful criminal economy, worth billions of dollars.

UK companies suffer from a loss of sales within the region and yet do not have the resources in SE Asia dedicated to IP protection and enforcement. Many smaller and newer British investors suffer from lack of information, resources and ability to handle the problem.

Unfortunately, even though there are multiple surveys and reports that discuss these issues it largely remains unchanged. More needs to be done to improve the messaging in relation to the harm caused by counterfeiting to SE Asian governments. Traditional IP lobbying approaches have not worked and so more tangible examples of losses and damage will need to be shown.

Customs IP border seizures are a far more cost-effective solution for SE Asia countries than trying to catch counterfeits through their criminal systems after these goods have entered the country, are broken down and retailed in small volumes.

While ecommerce transaction between China & SEA continues to grow, a proportion of it is made up of counterfeit goods. The increase in counterfeits in the market as a result of ecommerce trade was the single biggest concern raised by UK and international companies surveyed for this report.

Global lockdowns and border restrictions as a result of COVID-19 has accelerated the move online for both illicit and legitimate trade and accelerated the transformation of entire supply chains involving transportation, warehousing, distribution and packaging. Ecommerce has become the main platform for a wide variety of counterfeit products, not only for fake and substandard medicines, test kits and other COVID-19-related goods, but also for mainstream consumer products.

Ecommerce trade is dominated by SE Asian platform sales and cross border sales from China.

This latter component subdivides into:

More and more SE Asian platforms have cross border sales functionality and are allowing non-resident merchants, especially from China, to sell their goods online. One of the main problems for SE Asian platforms in onboarding and identifying the many Chinese traders that ship goods through logistics and fulfilment centres in China, which they use as their address/location, masking their real identity/location. This makes it easier for Chinese sellers to sell counterfeit goods on SE Asian platforms and is a particular challenge for IP owners in SE Asia trying to tackle remote Chinese merchants. The largest volume of counterfeit sellers however are local SE Asian merchants and drop shippers who source goods directly from China then resell locally.

To address the issue of imported counterfeit goods from China, as opposed to the pure domestic counterfeit issue, more can be done to engage directly with the ecommerce industry (as well as the wider logistics, social media, payment systems and online advertising companies that are also part of the ecosystem) and put in place further proactive online technologies and mechanisms to identify and address the problem. This includes platforms stopping all sellers (including Chinese sellers) appearing on platforms with no clear addresses and identity, as well as forcing sellers to pay deposits that are forfeited in the event of ongoing counterfeiting activity.

Additional legislative changes that clarify the liability of platforms across the region are also needed.

There has been no widespread shift of counterfeiting activity from China to other countries in the region. Where some countries, most notably Vietnam, have seen a slight increase in activity, this has been restricted primarily to products that are expensive to transport and can be re-filled in the country (such as lubricants and alcohol) and products that have established competitive local infrastructure and supply chains that can compete with China on price and quality (such as apparel, footwear and textiles). China’s strong counterfeit supply chain network, infrastructure, knowledge base and quality are not things that can be easily replicated in SE Asian countries just yet.

There was no evidence to suggest that China’s Belt and Road initiative has had an impact on counterfeiting activity in the region albeit it could provide a useful forum for building stronger IP and Customs cooperation.

The increased circulation of small parcels is fuelling regional cross-border logistics growth and has led to major infrastructure projects and initiatives that are reshaping air cargo, cross-border and maritime connections between China and the region. The increased investment in new technologies, changes to traditional cross-border shipping models and the increased availability of one-stop-shop solutions for Chinese sellers are making it harder for Customs authorities in the region to identify counterfeits and making it easier for counterfeiters to disguise their movements.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO UK) has engaged British IP firm Rouse (www.rouse.com) to study the cross-border trade in counterfeit goods between China and South East Asia (SE Asia), focusing on branded consumer goods industries in which the UK leads. This webinar updated a similar 2015 report, additionally covering developments in routes, the impact of ecommerce growth, the COVID-19 pandemic, and changing patterns in the SE Asian counterfeit trade.

Speakers included: Nick Redfearn, Rouse; Chris Mills, IPO UK; Anan Sivanantha, Bird & Bird; Claire Wood, RB Group; Desmond Tan, British High Commission and Conor Murray, British Embassy

Data Sources include: UNDOC, OECD, China GACC, SEA Customs, EU ASEAN Business Council, CBBC, ICC, QBPC, Interpol, Europol, UKIPO, EUIPO, Rouse, IP Komodo, Economist Intelligence Unit, Economic Times, Jakarta Post, Reuters, Xinhua, WTR, INTA, University of Groningen ITG, USTR, EU Commission