This article aims to discuss risk-management strategies to consider in protecting the intellectual property (“IP”) of Chinese businesses looking to enter the Indonesian market with the help of a local distributor or partner.

Generally, foreign brands rely quite heavily on their local distributors to expand into the Indonesian market – whether these are large, complex multi-nationals or young local companies expanding overseas . One of the most common problems faced is confronting unscrupulous local partners who attempt to reserve IP rights, that rightfully belongs to the foreign brands, to themselves.

Two situations that foreign brands may encounter include:

1. Squatters, who register various well-known brands without any intention of using them for the purposes of holding these registrations as future ransom; and

2. Distributors or local partners, who pre-emptively register the IP of their foreign principals to secure “insurance” during the re-negotiation of their contracts.

Accordingly, we suggest three solutions to effectively manage these risks. First, secure trade mark registration in the local market. Second, conduct due diligence on the local partner. Third, impose minimum contractual terms in the partnership agreement with the Indonesian partner

Registration of IP

Before entering into a market like Indonesia, it is critical to secure trade mark registrations as early as possible to avoid squatters. This is particularly important for the consumer and trade product sectors.

Trade mark registration may be used defensively and offensively. As a defensive tool, filing for trade mark registration at an early stage is critical to avoiding bad faith registrations made by squatters. Registrations filed by squatters could potentially exclude foreign brands from entering into the Indonesian market. Even if the foreign brand successfully purchases the IP back from squatters, it enters into the local market at a greater cost due to capital deployed to re-acquire IP that rightfully belonged to the brand.

Due Diligence on the Indonesian Partner

When conducting due diligence on the Indonesian partner, foreign brands should take care to check the following:

1. All trade mark registrations registered to the Indonesian Partner; and

2. All dispute(s) that the Indonesian Partner was previously involved in.

Please note when we refer to “Indonesian Partner” we mean the Indonesian corporate entity that will be contracting with the foreign corporate entity. It is also important to identify key individuals behind the Indonesian corporate entity and undertake a trade mark search against the names of these people for item (1). It is also good practice to check if these individuals are using their family member’s name to register for trade marks.

Minimum Contract Terms

After conducting the necessary due diligence, the question turns to how foreign brands can best protect itself against local partners (whether as a distributor or licensee).

As mentioned, foreign brands sometimes place too much trust in the local partner’s market knowledge which may result in unfortunate cases where the local partner pre-emptively registers the trade mark of the foreign principal in their own name without the rightful owner’s prior consent. This is done in the hopes that once the distributorship ends, the existing registrations may serve as leverage when negotiating for a distributorship or licensing contract renewal.

There are IP clauses that could help prevent this situation. The most basic ones include:

Note: Key individuals of the company (discovered at the due diligence stage) should sign a similar undertaking, with a clause stating this individual additionally promises that neither his nor her family members will use their names to register for the foreign principal’s IP.

Though these preventative measures appear simple, they are often overlooked. As illustrated below, we included two case studies demonstrating where and how things can go wrong.

Case Study A: Case no 28/Pdt.Sus-Merek/2017/PN.Niaga.Jkt.Pst

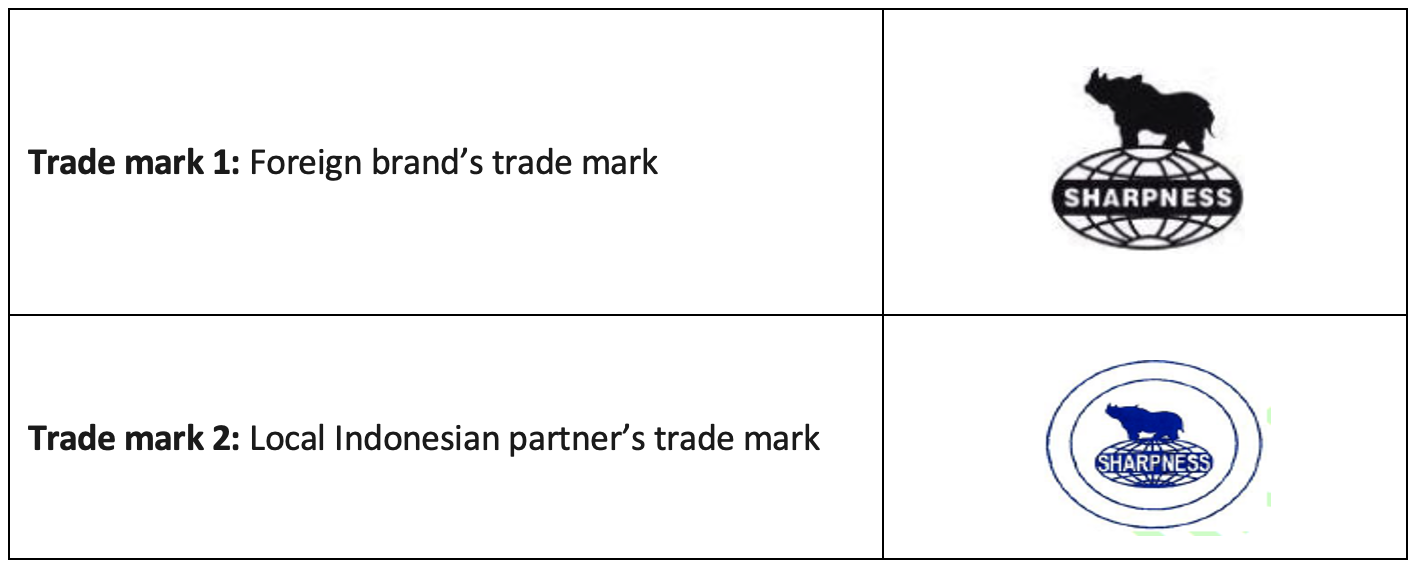

The relevant foreign brand is a Chinese company called HUBEI YULI, who owned the trade mark “Sharpness” (see Trade mark 1). HUBEI YULI then worked with a local partner to expand its branded sand paper products into the Indonesian market. After the termination of their business relationship, the local partner then registered a likeness of SHARPNESS trade mark (see Trade mark 2).

The local partner set up a local incorporated company called PT Sukses Bersama Amplasindo and assigned the SHARPNESS trade mark registration to this corporate entity. This company also appeared to operate the website named “www.Sharpness.co.id”.

During the first legal proceedings lodged against the local partner, HUBEI YULI only named PT Sukses Bersama Amplasindo as defendant. HUBEI YULI’s request was rejected by the courts as it ruled, as a matter of procedure, that it should have included the original applicant/assignor, the Indonesian partner, as a co-defendant as he was acting in bad faith when registering for the SHARPNESS trade mark.

During the second legal proceedings, HUBEI YULI named both the local partner and PT Sukses Bersama Amplasindo as co-defendants. HUBEI YULI lost at the first instance as the commercial courts ruled the evidence submitted to prove overseas registration (see Trade mark 1) was unverifiable as it was not original copies of trade mark registration documentation, but mere photocopies and website printouts.

On appeal to the Indonesian Supreme Court, HUBEI YULI successfully cancelled the bad faith application on the basis that the website printouts originate from official websites are easily verified. It is also likely that the bad faith conduct was apparent in this case as the local partner also copied the logo, not just the word element.

Though this case was decided on 15 October 2019, the partner appears to still be using this trade mark at the domain name “.co.id”. It is clear the damage caused to HUBEI YULI has long-lasting implications when it comes to re-claiming full control over its brand.

Key takeaway

This case demonstrates the importance of complying with all procedural steps when lodging an action against a local partner as there is little opportunity to rectify procedural defects once filed.

This foreign brand could have conducted trade mark searches and due diligence checks on the local partner and the background of key individuals behind the corporate vehicle.

Obtaining personal undertakings from the local partner or relevant corporate entity and key individuals involved (i.e., family members or high-level employees) that they will not register its IP would have provided an additional layer of protection. Particularly, when the “controlling mind” or “controlling individual” seeks to take his or her bad faith registrations elsewhere as shown here.

Case Study B: Confidential Case Where the Foreign Principal’s Technology Was Patented

A local partner may also attempt a scorched earth policy if he or she anticipates a foreign brand will replace the local partner with another distributor.

In this case, an American company supplied building equipment to a local company. The building equipment is to be installed as part of a system in buildings and civil engineering structures. The local individual registered a patent for the system that incorporates the equipment supplied by the American company. He claimed to be able to stop any third party from using the building equipment as part of any system in a building. For reasons unknown, the patent was granted, and the local individual tried to use the patent to prevent the principal from appointing another distributor in Indonesia.

The new distributor as well as end user of the building equipment were reported to the police, and this led to an arduous ordeal for the new distributor to expand the market of the American company's building equipment. It was only after many meetings and arguments before the police that the criminal complaint was finally withdrawn.

Key takeaway

This situation could have been avoided if the distribution agreement contained a clause that prevented the local partner to file for any IP (including patents) using the foreign brand’s technology. Even if the local partner intends to claim any IP registration, consent ought to be obtained from the foreign brand. The foreign brand should also be filed as a joint owner of the IP registration.

This case study ends with a clear message that foreign brands who do not implement protective mechanisms will fail to safeguard its interests by not insisting the application be filed under joint names.